Fuck Me, I’m Famous: A Nikkatsu Roman Porno Reboot Review

There’s been an increasing amount of books and articles in the past few years that take a stab at the “sex films” made in Japan since the 1960’s until way past the 80’s and 90’s. Few are both as encompassing and dreaded as the book The Sex Films: Japanese Cinema Encyclopedia by Yuko Mihara and Thomas Weisser, which has been criticized since its release in 1998 for being riddled with bad translations, wrong synopsis and false information. Nevertheless, in its foreword, written by Thomas Weisser, a phrase has become the definition of the pinku, roman porno and Japanese erotic cinema, and has been quoted in at least two books, as well as in countless articles, regarding this subject: “this unique genre may be Japan’s most important contribution to world cinema.”

While I can’t completely agree with Weisser’s words, I can certainly see what he’s aiming at, and the history of the genre throughout the decades says a lot about how unique, unrepeatable and strange the films that were made under the pinku label (whose name comes from the abundant presence of naked women, something that was categorized as “pink” by a Japanese film critic in the dawn of the erotic films as they approached mainstream). Because these films were part of the mainstream, they were severely looked into by the Eirin, a board that gave a seal of approval for the films to be distributed (they didn’t censor, they just made “recommendations” for the film to achieve the seal, without it, it was practically impossible for the film to be released in theaters commercially), but as long as they didn’t show any genitalia, they weren’t relegated to specialized cinemas, anyone could enjoy them if they paid their ticket.

In particular, the films made under the Nikkatsu brand (from 1971 until the late 80’s) the famed roman pornos (shorthand for “romance pornography” films with a sex scene every ten minutes, but heavy on plot, aimed at couples that could go together to the movies), had their own set of rules regarding the type of relations, the duration between sex scenes, but what was more important: the mundane nature of the characters, the relations and the portrayal of that sexuality in a society that was still too conservative regarding its relation to women and sex. The characters were, in most of the cases, normal, average Japanese people, living through their life, and having sex, because it was the normal thing to do. It was essentially a portrait of the private life of the Japanese.

The films produced by Nikkatsu that focused on these everyday characters were also the most profitable and critically acclaimed. One only has to look at the Apartment Wife series, which had over 20 installments since 1971, which chronicled the sex life of an unsatisfied woman while her husband was working. Or the Beautiful Sisters trilogy, which starts as a romantic triangle and ends up as a ménage a trois. There’s also a series of films that have received the translated title of Confessions of…, the most popular being the ones about an Adolescent Wife (a trilogy), but there are also those by a College Girl and another by a Female Secretary. Or also the classic Female Teacher films, which expanded over 8 installments in Nikkatsu’s heyday, among countless others with buzzwords like “office lady,” “nurse,” “love hotel” and “affair”… but also “rape,” “virgin” and “torture,” a side that was mostly related to the S&M and “roughie” films from the Nikkatsu, which also ended up being about the lower passions, fetishes and deviations of the everyday Japanese men and women.

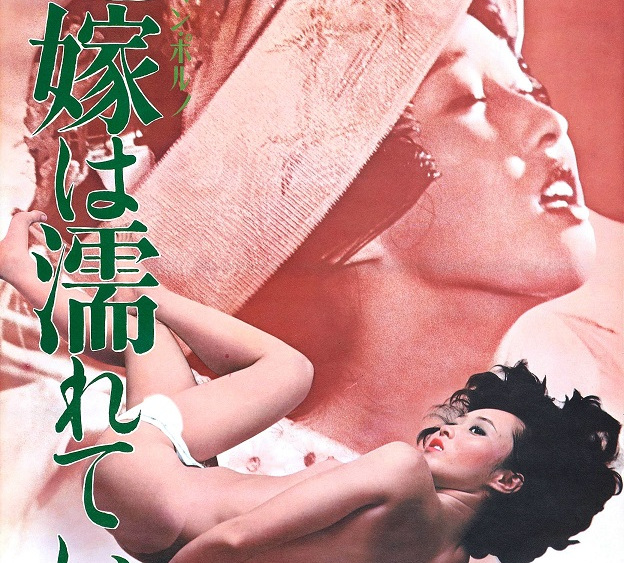

Three variants on the Female Teacher in Rope Hell poster.

Nevertheless, I am of the impression that these were far from conservative films. Sure, they are under the big umbrella that is pornography (the softcore kind, but still), so the problem with the male gaze is extremely present (especially with the vast majority of male directors working on these), but they were commercial films made with the intention of pushing the extremely conservative boundaries of Japanese society, that only recently had stopped treating women as second-class citizens (in many ways Japanese cinema chronicled that evolution with its focus on women and their stories, from filmmakers like Ozu and Naruse, going through the pinku eiga, and well into the 2000’s). The female characters were, dare I say, relatable and complex, and through their bodies they didn’t only entice, but also make you feel and think. The famous pinku actress Naomi Tani said: “the woman’s naked body must not only be seen as a sensual object, but must also be able to express emotion”

Naomi Tani

With years, some of the films became cult classics, exploitation markings of an era that couldn’t possibly return, but along comes Nikkatsu, knowing about the popularity that this genre was getting in the repertoire scene, as well as the DVD market, along with the avalanche of scholarly studies and books on the subject. In 2016, they kickstarted a project to bring the Nikkatsu Roman Porno back into the cinema landscape with a project they nicknamed the Nikkatsu Roman Porno Reboot. They took five directors (some more known than others) to make five films that had to follow two simple rules: sex or nudity every ten minutes and a tight budget/production schedule. Along with the new films, restorations of the old films were also making rounds in festivals around the world.

But the new films came into a new Japan, where some laws had relaxed, the Eirin Film Rating System has eased up in some regards, but at the same time it’s a country that has regressed in their sexual politics, with large percentages of young people not being interested in sex, as well as recent studies signaling that up to 25% of adults are virgins. How do you portray the sexual society of the common Japanese women and men in one that has less sex than before? The answer is: you don’t. You move towards the opposite, you move towards the outwardly, the open, the public, focus on people that are known, people that have sex with other people because they can “force their image” onto the others.

The clearest example of that is in Isao Yukisada’s Aroused by Gymnopedies (2016), where the protagonist is Shinjin (Itsuji Itao), a 50-year old art film director who finds himself bedding an enormous amount of women based on the simple reason that he’s a famous director. The film opens with Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1, one of the most cinematical of piano compositions (its use of piano makes it sound classic, but its note arrangement makes it incredibly modern and moving) while we see our protagonist looking out the window at his neighbor who starts to show her breasts while she touches herself, and we see him doing it as well, until the music ends, he finishes and heads out. He’s a director of “high-minded” films, but always with low budgets, he’s described as “a talented director whose films have never made money,” but everyone seems to admire him, beyond his actual monetary success, which doesn’t help when he finds that the main actress of his latest project doesn’t want to work with her co-star. That’s the starting point for us to watch his wallowing while he has sex with one of the members of his crew, then a student in one of his classes at university, the actress that dropped out of his movie and finally a nurse that’s taking care of his wife, who’s in a coma after a suicide attempt (this last sex scene happens in his wife’s hospital room, with Shinjin taking the nurse from behind and him screaming “watch me”).

All of these new pinku films have different genres, and this might be best defined as a drama, due to the intense depression that the main character exudes throughout every encounter, as if he were having sex just to set his mind free from the possible death of his wife. The most telling moment of the film regarding its lack of touch with normal everyday sexual life is when there’s a repertoire screening of one of Shinjin’s films, and while he answers a question about love, he’s confronted by an ex student who’s the boyfriend of the student he had sex with the day before. A fight starts between Shinjin, the boyfriend, the student and the actress, and all of them chase him out of the building, trying to either hit him or make love to him again. The chase sequence feels a bit out of place in between the intense drama, but it’s all a bit outrageous, particularly between the old man and the almost underage student (who’s a virgin, of course).

Also about a talented man that’s trying to get his mind away from things is Akihiko Shiota’s comedy Wet Woman in the Wind (2016), but here, the main character goes about it in an opposite way than Shinjin. Kosuke (Tasuku Nagaoka) is a successful Tokyo-based playwright that has built a makeshift hut from scrap material to stay in the forest near a small seaside town, trying to get away from women, whom he thinks are the source of all the problems that he’s had in the past. The first scene signals the rhythm of the physical comedy that will come, with a girl named Shiori (Yuki Mamiya) cycling down a pier and into the ocean, to then get out of the water and gets naked in front of Kosuke, who starts to break away from her as she’s asking to stay at his place for the night. She follows him as he goes towards his hut, and even after he denies her every advance, she hops on top of his head, to which he responds by throwing her to the ground. The film is filled with slapstick-like sequences like that, where the acrobatics go beyond the sex scenes and into small fights between the characters that are trying to resist each other.

It’s only with time that we know that Shiori is some sort of irresistible force and everyone is fascinated with the way she makes love with everyone but Kosuke, whom she’s trying to seduce and make crazy. But, why him? When Kosuke’s ex travels from Tokyo looking for the playwright, alongside a troupe of three young actors and a young assistant, one notices that the chaotic element that is Shiori comes to disrupt everything that surrounds Kosuke might be related to his fame and what he could do for Shiori, as she plays along with the actors, the ex and the assistant, trying to give off the sensation that she’s doing this because Kosuke might do something for her. It’s the night of the day that Kosuke’s ex appears that the whole thing turns chaotic: sex between Kosuke and his ex is hijacked by Shiori, suddenly turning into a threesome which slowly turns into a lesbian scene between the two women, Kosuke being kicked out of his own hut; hence, he approaches the young assistant (she said that she admired Kosuke’s work when she met him) and starts to make love to her, all of this while he looks at his ex approach the tents in which the actors are staying, leading them to the van and then fucking them inside the vehicle. That extends into the next day, when Shiori finally exclusively fucks Kosuke, then we see the assistant find true love with one of Kosuke’s friends (fucking inside his car) and the van in the highway stopping in the middle of the road so the three actors can fuck their director. Everybody fucks!

Similarly chaotic in its proceedings, yet with a bit more of a romantic-drama edge is Hideo Nakata’s White Lily (2016), which follows the weird master-student/mother-daughter/lover relation between ceramist Tokiko (Kaori Yamaguchi) and her apprentice Haruka (Rin Asuka). They live together and the apprentice is the one actually in charge of the ceramist school that they have, while Tokiko constantly has meetings, engagements, reunions and even TV appearances: she’s one of the top ceramists of Japan. Many years ago, Haruka appeared near Tokiko’s house and she took her in with her husband, since she was a lost child, but once Tokiko’s husband died, Haruka promised to be with her always saying, “I’ll accept anything from sensei.” This creates an unhealthy relationship between them, where Haruka suddenly realizes that she’s trapped by her promise, as Tokiko can come home with a man and make love to him while Haruka listens… and later Tokiko will pay a visit to Haruka’s room and make love again.

While not being the strongest entry in this reboot, the first sex scene in this film is actually the best of them all, a lovingly created lesbian sex scene that carefully avoids the male gaze by inserting some POV shots between the two women in precise moments of pleasure. When Tokiko and Haruka make love, the room disappears, first everything becomes black and then slowly white, music fills the screen and their moans become a realization of their desires. Instead of showing oral sex, we see Haruka licking a white lily, beautifully rendering the love and abnegation with which she performs this act. All of this is broken by the presence of a new apprentice, a young man named Satoru (Shôma Machii), who Tokiko instantly likes and wants for herself (even if he has a girlfriend). The movie devolves into a romantic triangle that’s filled mostly with Haruka’s suffering, especially after Satoru tries to drive her away by saying, “you think you’re constrained by sensei, but you’re the one constraining her.” The movie climaxes with a furious Tokiko forcing Haruka to give oral sex to Satoru while his girlfriend walks on them. Everything seems motivated by a fleeting sensation that being with sensei might be the best thing, why? Again, her known status might be the only answer at this point.

The vilest of these films is Dawn of the Felines (2017), directed by Kazuya Shiraishi, which follows the lives of three call girls in their sexual adventures. One could think that this would be closer to the more archaic, original point of view of the roman porno, but instead it just becomes a series of events that revolve around the idea that the agency at which these women work requires them to become more famous so they can get more money, hence, the theme continues, here using the idea of viral videos to spread the information about how slutty, fierce or good they are. The film manages to create some interesting stories for the three of them, but they don’t evolve beyond those initial constructions, turning into vessels for cruelty and misogyny.

On the other hand, the most revolutionary of these films is Sion Sono’s Antiporno (2016), which is entirely focused on the subject of the pinku film itself, like an ouroboros eating its own tail, the wild structure of this film becomes a commentary on the way that fame has eaten up every character in a sex film. The protagonist is an underage girl that wants to become famous by doing a porn film to escape her family history (a perverted dad, a suicidal sister, a stepmother that doesn’t care for her), all of this while the plot of the film she’s doing mixes with her reality (or the other way around?) where she’s a famous author being interviewed, subjecting her assistant to various acts of submission. Here the theme of fame is central to the plot, because it is in fact a denouncement of that path, becoming absolutely scathing in practically every cut, spelling out the way in which women have been historically subjugated in Japan’s society and how her superior stance has shed a light into her brain and has decided that becoming a whore is the best thing that any woman can do.

In many ways, the protagonists of all these films are (both male and female) slutty because they are famous or known (Dawn of the Felines exempt as they become famous because being slutty is what they do); the little or large power that they have over others is usually enough for them to be attractive and gather around all the sex scenes that the film has to have. In this modern society, one can’t have too much sex if you’re just an ordinary person, the only way to justify it is by having them be extraordinary, and in this particular case, they have to be extraordinary artists (ceramist, actress, playwright, director), and they at times might not even want that happening to them, but there they are, subjected to the rule of sex every ten minutes, living the life that no other human being could have, alluding to their fame as the only reasonable explanation for them to have a porno made out of them, as soft as it might be.

BIO:

Jaime Grijalba (@jaimegrijalba) is from Santiago, Chile. He's a freelance film critic/programmer/maker. He's written for places like MUBI, Kinoscope, Brooklyn Rail, among others. He's programming for the Valdivia Film Festival and the Santiago Documentary Film Festival. He's still trying to make his first film happen.