James Dean: Bisexual Martyr

Movie stars and martyrdom can often feel like the crude energy supplier of Hollywood legend. Rise and falls are textbook, stars quickly burning out can speak to lost innocence and potential, sacrificial lambs. But sometimes these stars were not lambs; instead willfully, if foolishly, they flew too close to the sun. No Hollywood legend felt so close to the story of Icarus than that of James Dean.

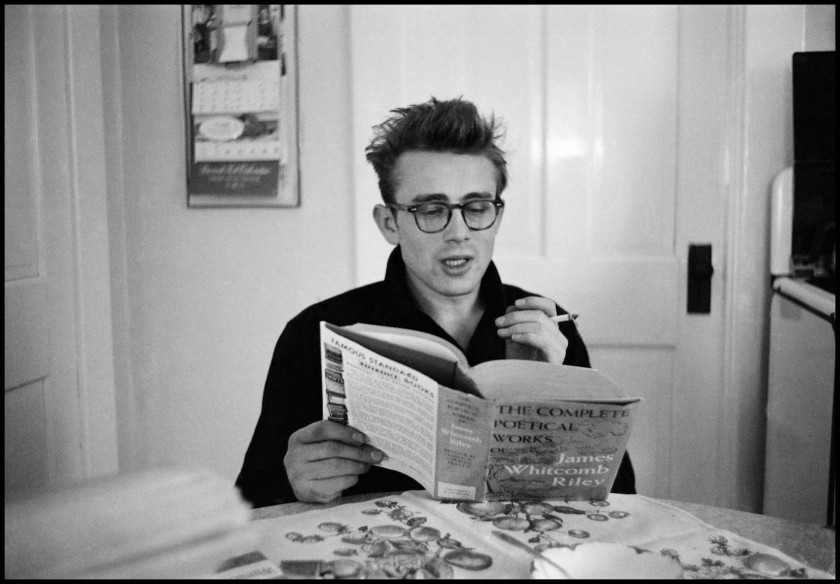

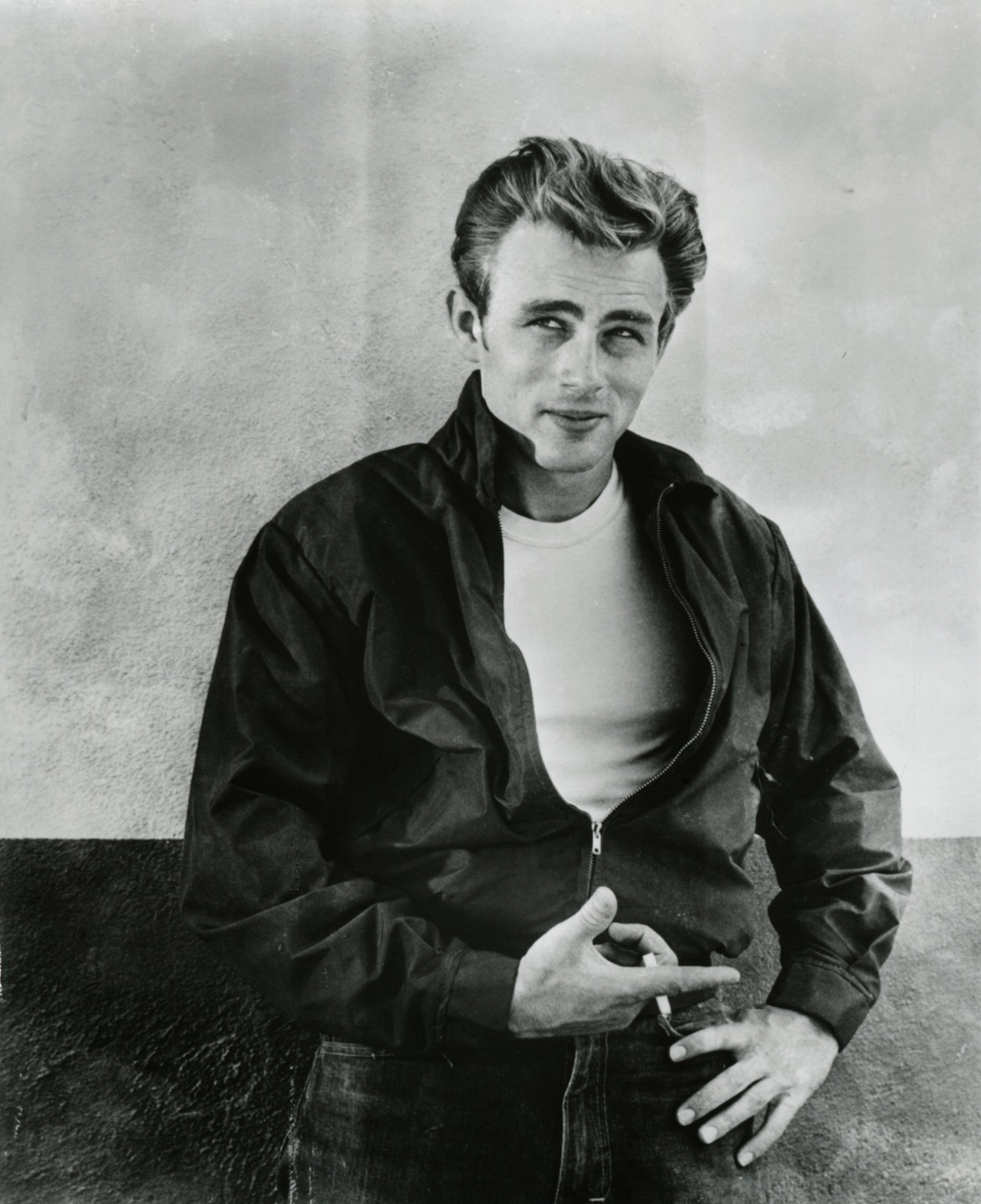

James Dean was a post-World War II icon whose appeal to teenagers made him endure through the decades. His movies and numerous photos taken by Dennis Stock represented an artist who was world-weary, solitary, appearing as somebody questioning the world around him, but still an enigma. Dean could be read as putting on the most performative postures in artifice or the realest one in an industry of fakes. There was something childlike to Dean in both those observations, everybody who came into his sphere had that impression of him as boyish. What was less distinct or concrete to Dean was his sexuality and romantic interests. His Giant co-star Elizabeth Taylor said he was gay. His friend Martin Landau said he was not. His Rebel Without A Cause director Nicholas Ray said he was gay. His acting peer Liz Sheridan wrote a whole book on their supposed romance, while also throwing in the caveat he was having an affair with a man. He had been linked to actresses Pier Angeli and Ursula Andress that were corroborated as being serious and physical rather than public “beards.” Author and Dean’s former roommate William Bast alleged that Dean at the very least experimented with men with Bast as a willing participant in one of the earliest Dean biographies, Surviving James Dean. Dean is claimed by all, tugged back and forth between two sexuality binaries while perhaps, more accurately, belonging somewhere in the middle.

James Dean & Pier Angeli.

The world changed in its understanding and openness to the fluidity of human sexuality and with that their gaze of Dean changed. But Dean had not changed. From the start, his small but potent body of work and early fandom featured an anti-conforming queerness that was closer to text than subtext. Meanwhile, his persona and martyrdom made him a quintessential avatar of teenage rebellion and Americana that appealed to the most straight-laced set of heterosexuals who still were drawn to a man whose sexuality still remains a topic of debate and fascination. But Dean’s cultural imprint preceded that discussion. His impact and instant martyrdom—only one feature film released when alive while the other two were posthumous—produced poetry (Frank O’Hara’s “For James Dean” and his many elegies on the actor are arguably the best, and earliest, work of art regarding Dean’s martyrdom), copycats in aesthetics by young actors absent of the otherness and allure, documentaries, and feature films based on Dean himself. Then there are the James Dean fans, disciples to a martyr who they admired, loved, and saw a bit of themselves in coming from all corners of life, straight and queer.

James Dean in The Immoralist.

Prior to being a star of the silver screen, Dean had achieved notoriety for a gay role on Broadway in 1954’s The Immoralist, a play based on Andre Gide’s scandalous novel as an “Arab boy” who seduces the married Louis Jourdan, whose marriage to Geraldine Page is disrupted by the bewitching presence of this mysterious, young force of sexual energy who is not overpowering nor effete in the way most gay stereotypes of the time were portrayed. Dean played on his youth and volatility that had prominent people in the entertainment industry take notice. Elia Kazan saw Dean in The Immoralist and immediately wanted to hire him to play Cal Trask in his adaptation of John Steinbeck’s East of Eden. Dean’s Cal is a rebel unloved, an unpredictable force of nature often walking hunched over and staring at the ground, at times in a fetal position, looking from the periphery at true human connections that he has had absent in his life due to being ‘damned’, feeling like nothing he does is right. That level of oppression into being made to feel like a sinner is very much in the parlance of being queer. The true love story of East of Eden is not Dean’s Cal and Julie Harris’s Abra but Cal and his father Adam, a paternal love while accepting Cal as different from the son he imagined. Cal is not a source and signifier of moral depravity like in The Immoralist, but he is a target of persecution from the moral hypocrisy of the ultimate family patriarch. Both characters can be queer.

East of Eden (dir. Elia Kazan, 1955).

Rebel Without A Cause took Dean from Steinbeck’s Salinas, California into modern times. Although the the studio had Marlon Brando in mind when in pre-production years before, Brando had aged out, over thirty by the time the film was in production. Frankly, Brando’s masculinity was tied to muscles and wife-beater shirts, an extremely blue collar identity ill-fitting for a teenager. Dean’s body, a scrawny 5’8’’ with raccoon-like dark circles under his eyes, made him appear both youthful and exhausted by life—perfect for the exasperated teenager who cannot seem to fit in, Jim Stark. Dean was ideal for the part and the fact that he goes from a character with the last name Trask to Stark (a re-arrangement of a few letters to the surname and they are exactly the same), feels pretty intentional and a signifier of Warner Bros. knowing what they had and cultivating to the strengths of their young talent.

Rebel was a “problem picture” arguably too modern for its time. Elements were cut and revised but certain aspects were obvious watching the film, namely that Sal Mineo’s Plato was gay and in love with Dean’s Jim. This is the most bisexual of James Dean’s films. The people in love with Jim Stark, Plato and Natalie Wood’s Judy, both come from feeling orphaned themselves, acting out from lack of parental connection in their own ways as teenagers. When Judy asks Plato about how he is in Jim’s inner-circle, Plato lights up gushing about Jim like a crush although under the label of “best friend”—a rush into a role when all three have only begun to know other for just a little over a day. Jim, the new kid in town with a vague past, is interested in both Judy and Plato. His kindness and un-jaded quality draws both in. But Jim is troubled. Toxic masculinity clearly has pushed his buttons to act out in violence that at one point he blames his inability to avoid trouble with other men on his not-very-masculine father (Jim Backus). As Vito Russo put it in The Celluloid Closet, “Dean’s Jim Stark is torn between society’s guidelines for masculine behavior and his own natural feelings of affection for men and women.” This movie openly mocks the nuclear family ideal of the Eisenhower-era 1950s, such as when Jim, Judy, and Plato hang out in an abandoned mansion they instinctually “role play,” Jim as the breadwinning man, Judy as the wife, and Plato as the homeseller. Together they are almost more of an alternative family than a menage a trois, but chemistry remains and cannot be entirely bottled up. Plato’s abandonment complex leads to most of the third act drama. In a way, Plato knows that he cannot be in Judy’s position of making out with Jim by the fireplace. At best, Jim Stark can just exist as that Alan Ladd photo in Plato’s locker, only for him to see. But looks exchanged between Dean and Mineo (a gay man in real life), are nevertheless magnetic and preexist Judy and Jim’s romance in the film, Wood’s Judy initially rejecting Jim’s friendliness preferring to conform with her boyfriend Buzz and his friend-group (a toxic, heteronormative gang no different from the structures they portend to rebel from and once Buzz dies, Judy escapes the group at a moment’s notice). Social structures in Rebel have been read as being pro-conformity, that a strong household could have prevented every tragedy that occurs in the film, from Buzz’s fatal “Chicken run” to Plato being shot at the Griffith Observatory. But Rebel is not a tidy work of art. Problems still linger. Nobody has won. Somebody important was lost and at the hands of authority. Plato is a martyr, for he is the true “rebel”—Jim gives Plato’s his red Harrington windbreaker, Dean’s biggest piece of iconography, out of love. Rebel is a plea for a redefinition of manhood. Jim nor Plato nor Judy are bad, but society pushes them to feel that way. They question and call out conformity of all forms because it seems to be if anything the source of suffering and misery.

Judy (Natalie Wood) & the ill-fated Plato (Sal Mineo) at the Griffith Observatory in Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955).

Leslie (Elizabeth Taylor) & Jett (James Dean) in George Stevens’ Giant (1956).

Giant is not usually the film that immediately has Dean fans claim as the source of their love affair on-screen, for this film is where he is a supporting character that turns into a villain halfway and then ages on-screen in caked makeup. An air of sadness often permeates those latter sections even more than director George Stevens intended because Dean himself never aged to that point as rags-to-riches, roughneck to oil tycoon Jett Rink. But this film is as queer as Dean’s previous two. This time Dean is orphaned in a literal sense, no blood family, with his parental figure being the butch Luz (Mercedes McCambridge), whose masculine qualities make her feel more of the family patriarch than her strapping brother Bick Benedict (Rock Hudson). Jett is lovestruck from the moment his eyes catch Bick’s new bride Leslie (Elizabeth Taylor). The unrequited love becomes a chip on Jett’s shoulder the size of Texas. It is not so much he feels entitled to be with Leslie, as there are many opportunities for them to state his feelings and he never does. He tries to avoid her catching his glances or clocking his outsized gestures, and underplay when she even accidentally seeing a shrine of her in his shack. There is a sense that he feels unworthy for her due to his class; the closest he gets to being mean towards Leslie is when she compares him to the Mexican-American laborers on the Benedict property and he acts out. Jett cannot hide his contempt towards what luck, life, and privileges Bick was given from the start—even from Leslie. There is something relatable in the jealousy and bitterness involved in how easy it seems from those of privilege in wealth, race, or gender have it. Queer people can be filled with that at times but there is only so much hate and self-hate one person can hold; there needs to be action taken for self-betterment in achieving the ideal you. Jett Rink’s transformation hits the most base of Freudian depths, he strikes oil after much labor, an explosion of black gold in the sky rains down on him and he becomes rich and powerful as he becomes covered in it all. But still, he sees himself as a “poor boy”, unable to reckon his past and regrets as the embittered old man he becomes, alone at the top.

There is something near transgender in these bifurcated before and after, poor and rich dichotomies to Jett Rink. This is further underscored by the fact that the Robert Altman film on a reunited James Dean fan club, Come Back To The 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, features a trans character in this James Dean fan club, literally called “The Disciples of James Dean.” Dean is treated like a Christ figure with his photos (including a Giant still that never appears in the film where Dean’s arms are extended around his rifle over his shoulders— basically Christ on the cross) and memorabilia everywhere at the 5 & Dime shop. The trans woman Joanne (Karen Black), who has had relations with men and women, is perhaps the clearest disciple of the group, a gender rebel, aligning with Jett Rink the character and James Dean the icon in changing her life to what she has always felt about herself. She has carved out and remade her own life for herself the moment she received an inheritance from her dead mother. But Joanne is full of regrets, haunted by a past in feeling repressed and having her love being unreciprocated, especially in her relationship with Sandy Dennis’s Mona, whose delusions have her convinced she mothered the son of James Dean when he was down in Texas to shoot Giant. What makes Joanne the rare on-screen non-martyr trans woman is that she not only lives but she’s learned. Joanne realizes that there needs to be a reconciliation with who she was back in the 1950s to who she is now as a woman and be open about that fact with those who remember her or chose not to remember her life and desires. Clearly she has been influenced by James and Jett, in what to do and what to be but also, crucially, what not to do and what not to be.

James Dean was intended by the Hollywood Studio System to be for everybody, but that does not mean his body of work and star persona miss in the essential appeal as a queer icon. His roles portrayed the pitfalls of conformism, traditional masculinity, and heteronormativity as nightmarish, untenable social structures with Dean himself as a symbol of being chewed up, exhausted. His martyrdom is not one of tragedy but resolve in the face of a society constantly boxing people as individuals into identities that are not that person. Dean often was a young man searching, wandering, seeking an alternative way of living that in many ways only existed after his death. His queer admirers took it to heart. Frank O’Hara’s “For James Dean” reads as an indignant plot of vengeance against societal norms, and arguably many readers, whom O’Hara (who, ironically, also died young in a tragic accident when struck by a car in Fire Island) lays blame for Dean’s untimely death:

“Men cry from the grave while they still live

and now I am this dead man's voice,

stammering, a little in the earth.

I take up

the nourishment of his pale green eyes,

out of which I shall prevent

flowers from growing, your flowers.”

Sometimes the best vengeance against a society that wishes to persecute you is to go on living as you really are. Embodying the idol you admire can be part of that nourishment when going against the world and for some of us, that will always be James Dean.

BIO:

Caden Mark Gardner is a trans male film critic from Upstate New York. He is currently working on the forthcoming book, Corpses, Fools, & Monsters: An Examination of Transgender Cinema with co-author Willow Maclay. He can be found on Twitter @cinematrans and Instagram @corpsesfoolsandmonsters.