As Long As You’re Known for Something: Outlaw Fame & Friendly Infamy with John Waters

John Waters wasn’t inspired to get into filmmaking due to the worship of any particular auteur. His love of William Castle—the carney’s Alfred Hitchcock—and his gimmicks were what pulled Waters into the medium. Film is largely the easiest art form to get outlandish and grotesque in (space saved for multimedia giants like GWAR), and when you have a lot to say about the insatiable thirst for fame, it’s the generally the splashiest route to take. While I love his films, Waters has never drawn attention to himself for being traditionally cinematic. Shots are competent and perfectly suited for humor, but all the real action lies in the dialogue, characters, wardrobe, subject matter and set dressing. Frankly, he’s just as talented a non-fiction writer and orator as he is a director, and as much as I crave a return of him to do just one last film, I also know that it’s a hell of a lot of energy to expend when you can make your money by traveling and storytelling the old-fashioned way in breathtakingly cool suits instead. That’s where a bit of his magic lies: John Waters has mastered fame so handily that he has full control over how famous he is at any given stage of his life.

I really can’t begrudge him not doing film anymore: gimmicks and the stupid intoxication of fame still thrive, of course, but it’s pretty boring now. Sassy social media accounts that “interact” with ticket buyers have replaced fake “in-case-of-fright” life insurance policies and Odorama cards in packed movie theaters. We’re reduced to endless videos and think pieces on 3-minute trailers while what our lizard brains really crave is the thrill of thinking that, somehow, a real snuff film could end up with fairly wide distribution. We still have fascinating actors, sure, but the real cool weirdos know to stay underground or just stream themselves: I just don’t know if I’ll see any of them with a three-picture deal and a TV special because what’s the point for them to even want that anymore? Plus, so many people know how the quickie Look-At-Me machine works right now that Andy Warhol’s maxim has had to be reduced to 5 minutes of fame for everyone because there’s a line, sweetie.

That said, if you’re not famous or infamous, then you damn well better be interesting. Wherever you are, there you are, sure, but with bells on if you have any respect for pageantry. Part of fame’s seduction is that it acts as confirmation that someone is interesting, noteworthy. You can be loathsome, but it’s accepted, maybe even lovable. It’s a changeable beast that adorably allows you to believe you have it tamed, just for a while.

The strength in Waters’ characters is that they’re already famous in their own minds, so that beast becomes a trained dog that’s already leashed and following them up and down the streets of Baltimore and beyond. Preposterous actions and outrageous costumes are really just fabulous window dressing: the real power behind the endurance of these films, and Divine’s legacy and Waters’ progression into a pop culture figure, in particular, is one of complete self-acceptance and confidence. The filmography of John Waters is ground zero for self-love. There’s no hard sell, which has helped Waters’ particular brand of peculiarity go mainstream. He’s so accomplished partially because he’s comfortable with himself to the point that not an ounce of energy has been wasted on self-hatred or judgment. He’s interesting, so he meets interesting people, made interesting films, marketed them with a sense of humor, and that kind of audacious purity was irresistible to the press and slightly more adventurous moviegoers.

He’s unquestionably talented, but there’s something intoxicating about Waters’ self-possession that’s made him a household name to the point of having an entire episode of The Simpsons centered around a character modeled on him. As the living embodiment of the antithesis to the tortured artist, Waters has long been in a unique position to both respect and gleefully condemn the very notion of American fame. John Waters can live wherever he wants to, but because he knows how to keep things interesting and he’s an artist, that doesn’t translate to his characters. Whether they give their lives for fame or gain local notoriety that’s bound to keep them in the same town forever, it’s never a pure, clean kind of success in Dreamland.

Dawn Davenport (Divine) from Female Trouble (1974) is the starkest, unmitigated example of Waters’ particular view of the journey of fame. From living an outsized, bratty life at home and school to petty crime—done in matching, sexy black outfits with her partners in crime, natch—Dawn’s undereducated (even forbidding her child to attend school) and overconfident, making her the perfect mark for anyone who can make some big and fast promises to make her the Next Big Thing.

Dawn was destined to be a star: she’s just too doomed by the blind desperation for it to see it. Soon she’s a drag Elizabeth Taylor with a bad marriage and frustrated success. Donna and Donald Dasher (Mary Vivian Pearce and David Lochary), a rich, glamorous couple who run the city’s hottest salon, finally take a vested interest in Dawn and her crimes. They want to photograph “crime and beauty,” and Dawn is only too happy to indulge in this sleazy 2-for-1 special. From pictures of her posing with her daughter’s unconscious body after domestic violence to an acid attack on Dawn’s face being documented before she can be hospitalized (and once she is, “It’s like an art opening!”) it’s a vulgar transaction that’ll end up with intravenous liquid eyeliner use, dismemberment, trampoline exhibitionism-turned-murderous, filicide, and, finally, the electric chair, which Waters has always considered “the Oscar of crime.” Dawn sacrifices her beauty and then her mortal body for immortal fame, and as she gives an acceptance speech before sizzling in the chair, we know this is a happy ending. “It won’t hurt. Nothing hurts!” Dawn also lets us know that it’s our interest in her crimes that made her exactly what she is, and she couldn’t make it without us. Watching is culpability; leering is practically aiding and abetting.

Once Harris Glenn Milstead and his Divine creation passed in the late 80s, Waters was able to find more mainstream actors who still had an edge or could be coaxed into invoking one thanks to the success of Hairspray (1988). One plus for this was that he started hiring real Hollywood stars, adding a squeaky clean kind of perversity on top of the dirty, odd kinkiness of the scripts. When it came to portraying the delicious vulgarities of fame, though, Waters found his biggest inspirations in blonde, middle-aged women: most notably Kathleen Turner and Melanie Griffith. In one of his most (eventually) successfully mainstream movies, Waters created his very own serial killer. Since there’s no way he’d settle for a cheap Charlie Manson knock-off, we got Serial Mom (1994).

“Beverly Sutphin refused to cooperate with the making of this film.”

While our antagonistic protagonist, Beverly Sutphin (Kathleen Turner), didn’t crave any kind of fame above being the best mom and wife in town, once infamy crept into her everyday life, church and all, she embraced it. It’s a true crime satire aimed at the consumer’s expense, and one of the best and most glaring examples of that judgment is the scene showing SERIAL MOM! merchandise selling like hotcakes outside of the trial once the suburban mom’s crimes get found out. Sutphin is attractive, a loving mom and wife, and she only murders rude people and maybe the stray witness. Gimmicks work just as well in criminal trials as they do in films, and nobody knows that like Waters, who even hosted Court TV’s 'Til Death Do Us Part as “The Groom Reaper.”

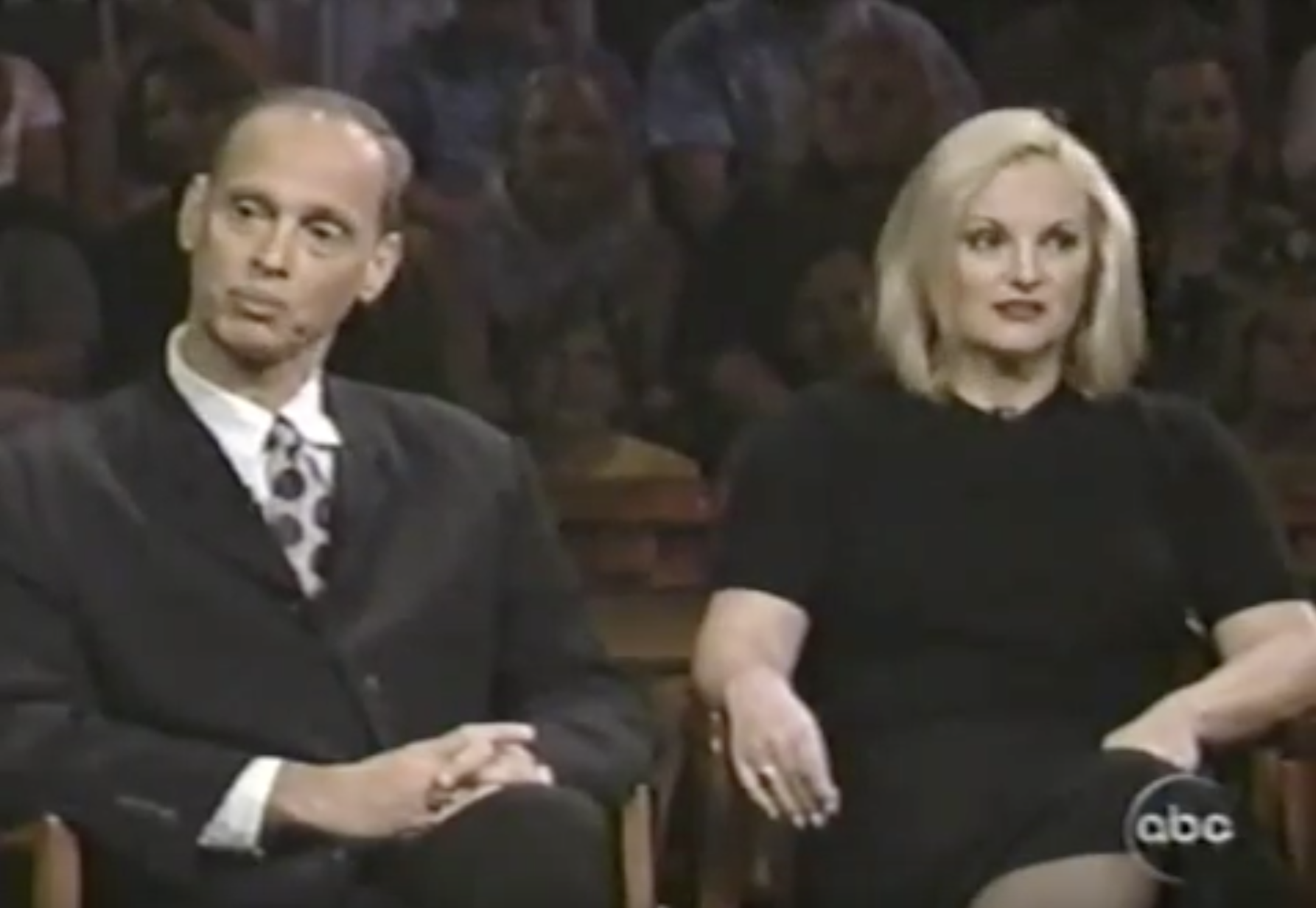

Sutphin plays everyone like a fiddle while she murders Patricia Hearst’s character right in a courthouse before giving Suzanne Somers (who will portray her in the movie version, of course) a look that may as well kill. Sure, it’s heightened and ridiculous, but full trials were playing out on television to killer ratings at the time. Satire rarely hits this hard and well with an innocent subject. And how times haven’t changed: now we park armadas of reporters outside of any splashy trial while making beautifully produced miniseries based on the celebrity crimes of 20 years ago.

Some may call Waters a prophet, and I probably would too, but more than anything he’s just very tuned in and empathetic. Waters has a deep-seated curiosity about the enormous variety of people and subcultures scattered like gems around society, and that’s led him to travel, read, and consume film and television widely.

A few years later, we got Melanie Griffith as Honey Whitlock, a beautiful and successful actress whose misery is matched only by the grief she ladles on to those who work for her. Her public persona is carefully honed to live up to her sweetie pie name, but behind closed doors, her star-studded existence is joyless and shallow. When renegade, under-underground filmmaker Cecil B. Demented (Stephen Dorff) kidnaps her to film an improvised terrorism film that’s kind of a cinéma vérité but on poppers affair, her fear and annoyance eventually melt away to relish the chaos and creative freedom that Crime Fame brings.

Waters continued his tradition of the protagonist/antagonists of the film being weird, mean and charming but completely misguided here. Both fame and crime have always had their strange, arbitrary rules and morals that eschew and embrace principles seemingly at random. You have to know the rules to break the rules, you have to have good taste to appreciate bad taste, and no one has married all of these together better than John Waters.

The enduring and endearingly odd friendship between Patricia Hearst and John Waters comes to a head in these movies when Waters finally, loose though it is, tells a (mostly) trauma-free version of her story in Cecil B. Demented. Proving herself as the ultimate good sport, Hearst appears in a small role as a mother of one of the outlaw filmmakers. Beyond that and her roles in his other films, Hearst would often do press for her films with Waters. A way to gain agency over her own infamous name or strange grasps at continued relevance, ultimately, that’s your own call to make. What’s important is that Hearst is always a pure character to Waters: he knows Hearst personally as a fully rehabilitated, terrorized human being who just wants to live a fun, normal life. A beautiful heiress-cum-victim-cum-militant-cum-tastefully dressed reformed citizen, she’s the living embodiment of what fascinates him.

While appearing in these movies does draw attention back to Hearst, it’s the kind of fame that’s positive, scripted, and fueled by a friendship. As often as Waters has gleefully thrown his characters under the bus, that’s never been his view in real life. A lover of gory Herschell Gordon Lewis films and never shy about violence in his own work, in real life Waters has spent decades working with prisoners and is a staunch supporter of criminal reformation. He’s unquestionably had more perspective on what being a truly decent person is more than the Moral Majority ever has, and that empathy, welded to his midwest common sense and rebellious artistic side, has given him the unique strength to see through everyone’s bullshit and portray it onscreen in a way not done before or since. The mysteries of fame crumble under that much objectivity. Sure, it’s still fun to look at, but it becomes more hilarious than alluring, and in Waters’ filmic world, you can’t crave fame without a personality disorder. In real life, Waters knows it’s more complicated than that, especially with people like Hearst, the friend he’ll gleefully use Kathleen Turner to murder, who are people who have been on both sides of the mountain and know how to take a joke for some art. It’s fame at its most controlled, useful dosage, and it’s sadly rarely prescribed.

John Waters went from gaining widespread notoriety for being a dirtbag hippie looking guy filming a drag queen eating dog poop onscreen to giving keynote speeches at college graduation ceremonies as a famous besuited fashion icon in one single lifetime. Any air of controversy he’s had always stemmed from having fun and taking risks when he was young, never from abusing or taking advantage of people (beyond what happens when you put your friends to work in a weird, no budget movie). He gained a mainstream success to the point of having successful Broadway shows made after his work, and he’s still widely seen as a weirdo director.

In Pecker, Edward Furlong plays the titular role of a young, shy, sweet kid from a small town randomly hitting it big with his outre photographs. As the high-falutin’ New York City art scene starts pulling him in and his fame grows, his girlfriend Shelley (Christina Ricci) warns him: don’t become an asshole. Waters gives the advice that he took himself.

I have a theory that naturally cruel and narcissistic actors aren’t great at portraying villains because they can’t even pretend to see themselves in that kind of role; basically, they’re just too good at self-delusion. Empathetic, thoughtful people, on the other hand, usually know exactly how assholes act and have a Library of Congress-sized backlog of empirical experiences to work off of, and I think that’s true for John Waters as a writer and director. He pays attention, he takes stock, distills, and gives us candy-coated killers and hilarious child beaters because he knows exactly how horrifying those people really are in person. When it comes to stardom, Waters equally treasures A-list stars, outsider artists, intellectuals, murderers and small-town legends. Everyone is there, and that’s why his films are as comforting as they are bizarre.

Waters had to be seduced by the magic and anarchy living inside the ephemera surrounding the cinematic experience itself to want to create in it, and we’ve just demanded his return rather than tempting him back. At this point, is fame even fun anymore? Being famous seems to have morphed into the same thing as being rich and privileged rather than those things PLUS living a wide, weird, outrageous life. Not only that, but today’s famous folk are also paying the piper more than ever with insatiable social media and a 24-hour news cycle. Everyone looks younger but seems more tired.

John Waters’ Rules to Becoming Famous

Exaggerate yourself

Hype yourself

Use your family

Move to Europe

Be an animal (A literal one, like Lassie or Paddington)

John Waters’ Rules to Staying Famous

Have sexual problems

Get sick

Be unhappy

Kill somebody

Die

“After all, wouldn’t you rather be dead than unknown?” - John Waters

[John Waters’ Rules to Becoming and Staying Famous from Crackpot by John Waters, 1987.]

John Waters once said there just weren’t enough celebrities, and some kind of evil genie monkey’s paw must have grasped a copy of his book Crackpot and made too many celebrities—and they used about three different cookie molds to whip them up and stopped there. So where does fame go from here? What’s the recipe?

I revere John Waters. I obsess over his work as much as I enjoy it. I think he’s a fascinating, fun, and very smart person. All I’ve ever wanted is more of him. Still, I don’t think that was ever his ultimate goal. Waters has become an internet quotation god thanks to his bon mots like “If you go home with somebody, and they don't have books, don't fuck 'em!” Now, I don’t know about you, but that’s clearly advice from someone who gives a shit. It’s funny, but it’s true. He wants you to seek out other people who are curious, strange and see outside themselves. He wants us to make and see fucked up films. He wants us to have open minds and hearts to criminals who have spent decades in prison trying to make good. He wants us to see a notorious figure on TV and picture them as a funny movie star who can give people hugs on the red carpet. He doesn’t want the weirdos to be lonely. He wants bland, safe people to see the absurdity inherent in obsessing about rules and fitting in rather than, well, their real obsessions. Waters knows that inhibition and truth are fucked up and amazing bedfellows. He wants to leave the world stranger, kinder, kinkier, and more open to its queerness than he left it, and if you’ve embraced his work on any level, I think you know that he’s done that.

Do John Waters proud and continue the thirst for thirst, knowledge, and fame. Make it your own fame, though. Make us come to you. Be a fame hag for people making YOU work for it. Don’t be generic or miserable. Let’s pretend we were never assigned anything.

BIO:

Stephanie Crawford is a freelance writer, full-time editor, and a-lot-of-the-time podcaster living in Las Vegas. From St. Martin’s Griffin to a column about Tales from the Crypt, that loopy kid will write just about anywhere about just about anything, which is why it’s important to visit her work at House of a Reasonable Amount of Horrors.