‘Love is built on banal things’: sex and sacrifice in THE PIANO TEACHER

“Cruelty, the lack of consideration of the strong for the weak, and the master-servant relationship, in the Hegelian sense; these are my themes.” So said Austrian author Elfriede Jelenik, author of The Piano Teacher, in an interview with the Financial Times following the publication of the English-language version of her novel Greed. Just two years prior, Jelenik had won the Nobel Prize in Literature - a decision which saw the resignation of one of the eighteen life-members of the Swedish Academy, Knut Ahnlund, in protest of Jelenik’s work. “Whining, unenjoyable public pornography,” was how Ahnlund characterised Jelenik’s books in the Svenska Dagbladet newspaper, “[which has] caused irreparable harm to the value of the award for the foreseeable future.”

Given the castigation of Jelenik’s work and the myopic, intensely perverse viewpoints that characterise her novels, it’s of little surprise that The Piano Teacher drew the attention of director Michael Haneke for his first adapted screenplay. Much as Jelenik has been criticised for her unstructured narratives that make use of characters’ thoughts and observations over plot, Haneke has been dogged throughout his career by a vocal minority over the violence and impenetrability of many of his films (a particularly scathing Slant review of 1997’s Funny Games closed with “while watching one of his films, there’s always a sense that he thinks he’s above his characters, his audience, and scrutiny”). In Haneke’s hands, The Piano Teacher pries apart a seemingly ordinary life, and leaves the audience observing the myriad ways sex and violence festers beneath the surface.

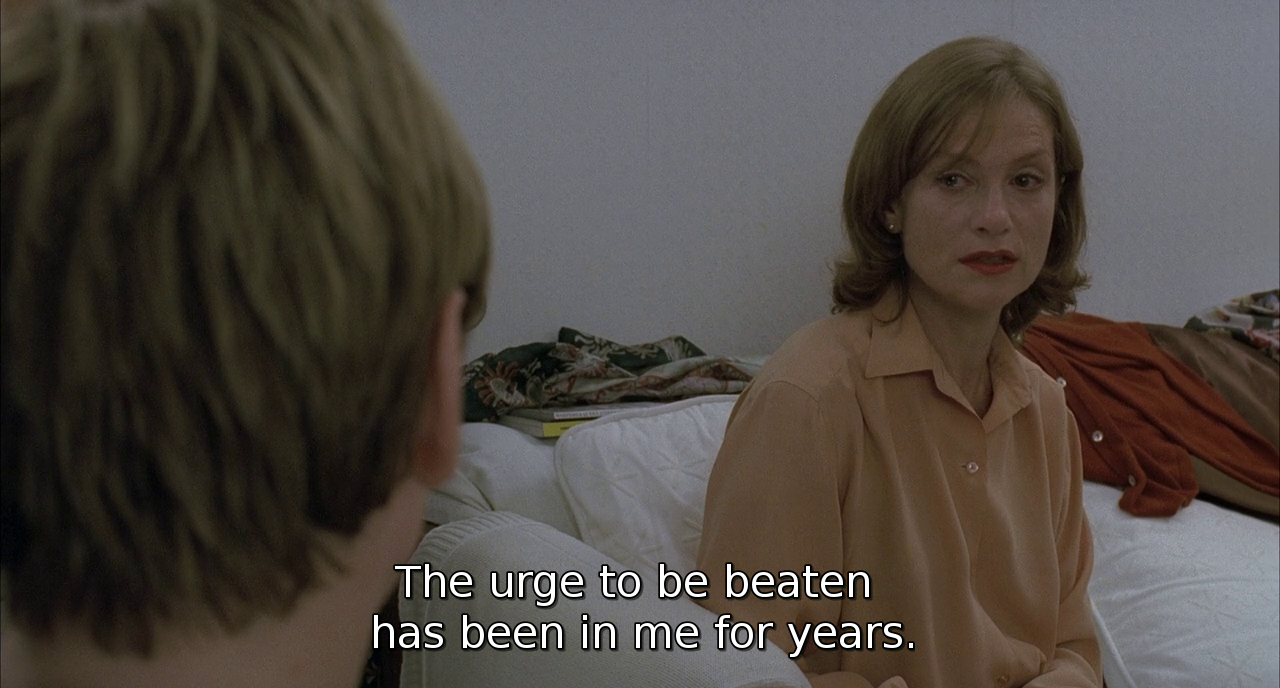

Erika (Isabelle Huppert) eyes her newest pupil, Walter (Benoît Magimel) in Michael Haneke’s The Piano Teacher (La Pianiste, 2001).

That seemingly ordinary life is Erika Kohut’s (played by Isabelle Huppert), the titular piano teacher, who works at the prestigious Vienna Conservatory. By day, she teaches students the piano, in turns an indifferent spectator and obsessive saboteur to their chances of success. By night, she is trapped in a cloying and claustrophobic apartment with her mother (played by Annie Girardot), who criticises and soothes Erika like a young girl. When this routine is disrupted by a newcomer to the conservatory, Erika’s life begins to unravel, as her masochistic sexual fantasies begin to bleed into her daily life (in one scene, quite literally).

One of the most remarkable things about The Piano Teacher is that for a film so centred on sexuality and perversion, it features very little sex. There is no glorification of the pornographic; as Haneke noted in 2003 interview, “I would like to be recognized for making in La Pianiste an obscenity, but not a pornographic film.” To make this film pornographic would strangely be to make it palatable - instead, we are left with the obscene, the out-of-frame horrors that speak to so much more of the characters interior disquiet. Erika’s perceived deviance is, for much of the film, acted upon alone - in acts of masochism, cruelty, and voyeurism and it’s clear that her pleasure is the pleasure of a fantasy; she wants to watch, and think, and imagine, but not to feel. In one of the film’s most memorable scenes, Erika waits, cross-armed and impatient, outside of several black, closed doors in a shopping mall. As the camera lingers on Huppert for longer, more of the setting becomes apparent - swathes of men lurk around the same shop, curiously hovering around her. At the edge of the frame, magazine titles become clear - as do the naked women on the front of them. She finally enters through one of the black doors, settles into a private booth, and hardcore pornography takes over the screen. Barely moving, face expressionless, Erika reaches into the nearby bin and taking out a handful of used tissues, holds them to her nose in gloved hands, breathes deeply, and continues to watch. At no point does she touch herself, or seem to receive any gratification. She studies the act like she studies the piano, but with no prospect of putting it into practice.

Jelenik described Erika as something that "remains on the road, like a greasy sandwich wrapper, perhaps fluttering slightly in the breeze. The paper can't get very far, it rots away right there. The rotting takes years, monotonous years." And Erika’s position as the paper on the road is deeply tied to place (Austria has long-been the focus of Jelenik’s work and also where Haneke was raised and studied). Her work is precision and her life is routine, and The Piano Teacher shows us what lies beneath that pristine Vienna surface; the hotbed of sexuality and seediness and perversion accessible to someone like Erika. Erika’s life is high and low culture, at odds with each other and struggling for space; the concert halls of Vienna to the dark back alleys of S&M.

After watching pornography in public, her next act of perversion is at a drive-through theatre, where a young couple are in a car having sex. We do not see much of the act, more focused on Erika’s curiosity and attempts to get closer. When she is close enough to the car to get a proper view, she is moved enough by the site that she squats and urinates, alerting the man in the car who Erika narrowly escapes. Erika’s gloved hands, her stillness watching pornography, her inappropriate response to seeing sexual stimulants - all show Erika as someone fascinated by sex and masochism, but unable or unwilling to receive pleasure herself outside of fantasy.

It’s when the fantasy becomes more tangible that Erika’s grasp of pleasure and control of her sexuality slips, and The Piano Teacher allows us to see the devolution of desire when fantasy is made reality. In his 2006 documentary The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema (which touches briefly on The Piano Teacher) philosopher Slavoj Žižek talks about the excessive reality of our fantasies and the fragility of the liminal space between fantasy and reality. Žižek says that for Erika, “fantasy is the explosion of unbearable desires”, and it is these unbearable desires which see Erika escaping to watch porn or stealing seconds away from her mother to self-mutilate. It’s also what brings her to Walter Klemmer (played by Benoît Magimel), a young engineer who wants to learn the piano, brilliant despite his casual and light approach to the study which frustrates Erika, moved despite herself by his audition for the conservatory. He openly and boldly desires Erika, challenging her and propositioning her lesson after lesson despite her resolute denials. In any case, Erika is quite clear that she cannot give what it is Walter desires, and that he should not want what it is she fantasises about. Ultimately, these desires become quite literally unbearable for Erika, who details everything she wants from Walter in a letter she asks him to read. In The Piano Teacher, the actualisation of fantasy is what destroys the desire.

While physical sex acts are not frequently present in The Piano Teacher, they are described in stark detail in Erika’s letter: “adjust the belt by at least two or three holes. The tighter the better. Then, gag me with some stockings I will have ready. Stuff them in so hard that I'm incapable of making any sound. Next, take off the blindfold, please, and sit down on my face.” Walter reads Erika’s letter, and stumbles and scoffs his way through her desire laid bare. As Walter looks up from the letter at Erika, his eyeline puts his gaze to the left of the camera. When Erika looks up, she is looking directly into the camera, and we’re held there for several seconds as Erika stares, expressionless. The scene isn’t dissimilar to those in the music practice rooms that characterised their previous interactions; Erika as teacher, Walter as student, learning what it is Erika wants from him. One line from the book that didn’t translate to the screenplay can sum up Erika’s confession to Walter: “the first thing a proprietor learns, and painfully at that, is: trust is fine, but control is better.” Erika trusts Walter with her desire, cedes her control, and ultimately loses both.

The masochism of The Piano Teacher extends far beyond Erika’s own sexual identity, and relationship with Walter. Rather the entirety of Erika’s world is built upon unequal relationships - the ‘master-servant’ relationship as Jelenik put it. Erika is servant to her mother, her students servant to her. And while all of the film’s violence and destruction is pointed towards Erika (and most often, by Erika), there is one scene where this violence is projected outwards. Erika leaves a recital and lingers in the cloak room. Much like several other scenes in the film, we see Erika acting in seemingly banal ways unsure why we’re watching until suddenly, sharply, her actions come into focus. In the cloak room, Erika searches for a few minutes, finds a cloth, glass, and uses both to crush and contain the glass shards. When we hear a scream off-camera, we’re aware something very wrong has happened - the girl playing piano, who Walter briefly showed kindness too, is holding her bloodied hand, scratches and punctured by the glass Erika placed in her coat pocket. Erika deals in the currency of pain and mutilation and only when it’s turned outward do we see the extent of Erika’s destructive tendencies and seeming lack of remorse or feeling.

Outside of her relationship with Walter, the dominant figure in Erika’s life is her mother (who has no name other than The Mother in both the novel and the screenplay). Her first love story, too characterised by dominance and submission. Erika is subsumed by her mother; her money is her mother’s money, her talent is her mother’s talent, each and everything she has is not ever her own. Erika’s attempts to buy a dress are seen as sacrilege - a defection from the purity of art, and seen as an attempt at sexuality that isn’t possible in her mother’s eyes, not while Erika must give her all to the piano, to art. Jelenik writes that “No art can possibly comfort HER then, even though art is credited with so many things, especially an ability to offer solace. Sometimes, of course, art creates the suffering in the first place.” It’s no wonder Erika finds sexuality in the darkest, most hidden corners of herself - there is no room in her life to express anything other than her art.

It’s this dependency and subjugation which pushes Erika to her perversion - some way of acting out and erasing her subjection to her mother. The book, even more so than the film, centralises the relationship between Erika and her mother, and the stunted psychosexual development of Erika is furthered by sharing a bed, home, and life with her mother while her father is in an asylum. Even with the clear codependency and emotionally abusive nature of their relationship evident, it’s still shocking when Erika throws herself on top of her mother and tries to consummate their relationship after Walter ridicules her letter, and symbolically return to her mother’s body, before being forcibly removed and rebuffed. The next morning, mother and daughter continue as if nothing had happened; a family repressing the torments and toxicity of their relationship for the appearance of normalcy.

Both key figures in Erika’s life come together in the film’s horrifying climax. Walter, disturbed by Erika’s desire and brimming with impotent rage at her unwavering control of their relationship, arrives at the small apartment Erika shares with her mother, unannounced. As Erika blocks off the connecting door from her mother, we see Walter beat and rape Erika, ostensibly acting out the fantasies Erika had shared with him, as her mother yells and cries from the other side. When Walter leaves, Erika crawls to the door and lets her mother in, making no attempt to hide her bloody nightgown or body. Throughout, Erika doesn’t say a word. “Will you be alright?” Walter asks. “Do you need anything?” Silence. “See you, then.” And he leaves. Even in the context of wanted sexual masochism, and Erika’s stated desire for subjugation, Walter’s actions are unmistakably rape (though many reviews at the time would characterise the scene as ambiguous, a home invasion, beating and sex act do not in my opinion lend themselves to an interpretation of consensual sex). The desire that Erika owned and made herself open to is stolen by Walter’s actions, and we see his transformation from being disgusted by Erika’s desire to punishing her for it.

In the context of the film, Erika’s actions are difficult to infuse with emotion or greater meaning than what we see - that is, Erika proposed a purely sexual, determinate relationship, and her sexual liberation was punished by a man who hated that she prioritised her perverse feelings over his. But we do not see hatred from Walter or Erika, or expected emotions after such a bloody, violent encounter; in typical Haneke fashion, the ending to The Piano Teacher is deeply ambiguous. Erika (bruise blooming over her eye but otherwise put together) is on the way to the conservatory where she is to fill in for a student at a concert. As she waits in the foyer, looking for Walter, he and a group of people come rushing in, late to the recital. He does not pause, barely speaks to Erika, turns around as he’s climbing the stairs and smirks, jovial and distinct from the person who raped her the night before. Erika is still, watching him, but he does not turn back again.

Now alone in the foyer, as everyone is inside the auditorium to watch the concert, Erika pulls out a knife, off-screen, and stabs it into her chest. There is a brief shot of anguish on her face, the most expressive we see her for the whole film, as she forces the knife in before pulling it out, a thin red line immediately evident on her cream shirt. She puts the knife back in her purse, and after a second or two, her eyes flit around to make sure no one saw. She swallows, her eyes shift, and she brings a hand up to her chest to cover the wound, as if coming back to herself after the cut. The camera shifts to a long shot and from behind the the double doors of the conservatory’s exit, we see Erika approaching, walking quickly as the blood stain blooms. She turns left, walks down the street off-camera, unnoticed, and traffic passes by, like nothing had happened. The paper fluttering in the breeze that people don’t notice.

The closing scenes show that even after Walter’s barbaric cruelty, Erika still literally looks out for him. And instead of punishing Walter for his abuse, Erika turns the knife to herself, penance and flagellation for allowing herself to be at the mercy of someone else. In Erika we see the rigidity of the masochist, allowing herself punishment without pleasure. And Haneke doesn’t indulge in the gratuity or pornography of the masochist; her mutilation is just made clear to the viewer, the obscenities evident but never the focus. Erika is always the focus, and the strength of Huppert’s performance is in the small moments of pleasure and despair we see in Erika’s otherwise tightly controlled persona.

Both Jelenik’s text and Haneke’s film show the audience different Erikas - in Jelenik’s words, we see the more frantic, explosive Erika whose mutilations are vast and vivid and accompanied by ceaseless thought and exposition and movement. In the film, however, Erika is a creature of stillness, her punishments neat and fastidious like the rest of her life. And in both, Erika is a masochist, but Haneke makes a masochist of his audience - watching scenes of calm, prosaic movements, piano recitals, shots of walking, milling about a cloak room, watching a hockey match, each in turn ending in violence or perversion.

Watching The Piano Teacher is to give yourself over to the idea that there will be no single neat psychological explanation or interpretation given to you - but that there are many of them, for the audience to unpick. At the end of the film, there is no satisfying understanding of Erika, her relationship with Walter, or her mother, or anything. She just leaves. So perhaps, as Erika says in the film, “love is built on banal things” - and in loving The Piano Teacher, we learn not to take those banal things at face value, lest we miss what lies beneath.

BIO:

Olivia Smith is a writer, and does several other things quite well too. You can find her over on Twitter talking about films, all the music that makes her sad, poetry, and other queer stuff @livspills.