LOVE - ZERO: Sex, Sadism, and Obsession in Hisayasu Satô's Gay Films

If I had to narrow down my many gripes with most queer film canons to just two big issues, it would be that picks tend to almost always be western films, and almost never sex films. This is unfortunate, not just because it pushes the same bland western art movie focus that dominates much of contemporary film discussion, but because it means a wide swath of truly great films are swept under the rug completely, forgotten even in cinephile circles and rarely given serious critical consideration. This is especially true of films that tick both boxes, and as such, Hisayasu Satô is a filmmaker whose contributions to queer cinema go overlooked by most. That’s a shame, not just because it’s indicative of a culture willing to ignore ‘disreputable’ movies, but because three of his gay films just so happen to be three of the very finest I’ve ever seen.

Like many exploitation greats, Hisayasu Satô’s work is deceptively easy to write off as pure schlock. As one of the so-called ‘Four Heavenly Kings of Pink’, he’s mostly known for his incredibly perverse softcore sex films, often sporting obscene titles like Unfaithful Wife: Shameful Torture, Pervert Ward: S&M Clinic, and Lolita Vibrator Torture. Through them, he’s got a reputation as a sort of no-budget provocateur, working in the confines of sex films to present shocking visions featuring everything from beastiality to auto-cannibalism, all done with a singular wild visual style and complete lack of filming permits. However, Satô is more than just some shock artist. His films are often bizarrely paced, stripped-down narratives with a heavy emphasis on depressing atmosphere over straightforward eroticism, and he often uses sex scenes not just for thrills, but as smaller pieces informing (usually) depressing ambiance. It’s rare to find a Satô film with a truly happy ending, and most times the protagonists’ quests end in pain, misery, or even mutilation and death.

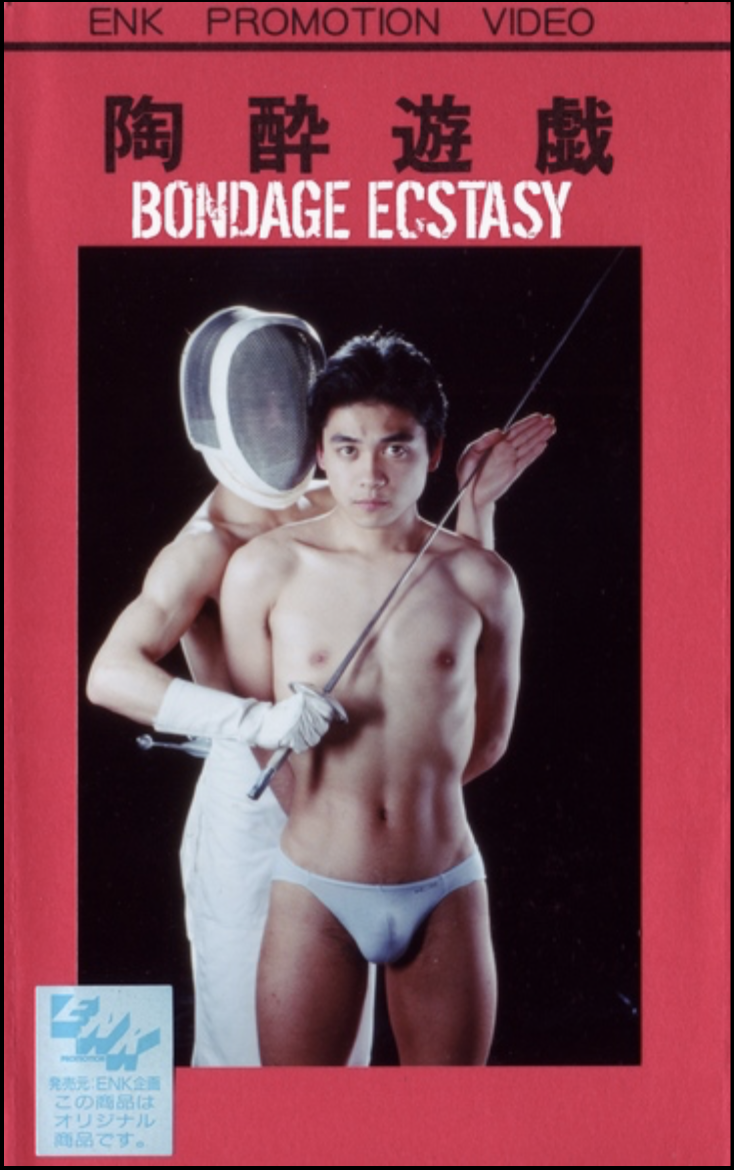

While it’s true that the majority of Satô’s pink films are made for a heterosexual audience (including a few lesbian films which, despite their subject matter, are still clearly marketed for straight men’s titallation), he did direct a few ‘male’ movies for Japan’s premiere studio for male-on-male pink movies, ENK. The handful he did there are every bit as strange and nasty as his straight movies - and it just so happens that three of them are among the best works exploring carnal obsessions out there.

The three films - Bondage Ecstasy (1989), Muscle (1989), and Hunters’ Sense of Touch (1995) - all focus on men driven by their lost loves, loneliness, and all-encompassing obsessions. The most straightforward example of these thematic concerns can be found in the former, which is also perhaps Satô’s most straightforward example of gay erotica. It follows Nakata, a salaryman stuck in a draining job, with no greater sense of purpose or belonging. Things change when he has a chance encounter with his high school fencing club rival/former lover Shirakawa, who is now in a relationship with a young woman named Takako.

While Bondage Ecstasy starts as a more traditional erotic drama, with Nakata and Shirakawa briefly hooking up after their first meeting before breaking away, it doesn’t take long for it to reveal its true intentions. After Nakata drifts to sleep while reading Kafka’s Metamorphosis (one of Satô’s many not-so-subtle winks to storied works in his films), he finds himself transformed into an insect in his dreams, witnessing men engaged in heavy S&M play - and not just any men, but cruel figures from his life, including his violently abusive boss and a local street tough who menaced him years ago. He dreams of them stripped, bound, and whipped, with his fly possessing the doms of each scenario, using his fantasies to reclaim the control of his autonomy he can’t achieve in the real world.

These sequences do basically all of the heavy lifting in terms of the film’s prerequisite erotic content, but more than that, they serve as the rosetta stone for all of Satô’s gay films. His films are obsessed with depicting the division between his protagonist’s desires and their realities, between their imagined perfect relationships and their brutal reality. In Bondage Ecstasy, things are more simple - the reality is that Nakata’s chance to be with Shirakawa is long gone, and his fantasies are the outlet for his desires, the rough S&M he used to play with Shirakawa (“We used to use rope, didn’t we?”) recontextualized under glowing neon pinks and blues. It’s a fairly clear divide between the two halves until the climax, in which the former lovers finally meet for a fencing duel to settle the score from their senior year. It’s a draw.

That’s when things begin to shift. The two are suddenly stripped down, embraced with the ropes out, the arena used for the death of their rivalry recontextualized into the birthplace of their second chance at love. Or maybe both at the same time, as when the ropes are untied, they rise back up, clad only in their underwear, pick up their swords, and prepare for one final duel with their lives on the line. And stare down, swords raised. And Takako walks in to the arena, stepping between them. And without hesitation, they lunge forward, and the sword tips meant to pierce each other’s flesh instead impale her.

Then Nakata wakes up. There’s no sense of shame, or confusion, or disgust over his fantasy of death at the hands of his partner as the ultimate symbol of love. There’s only the hurt that his visions aren’t reality, that even a bloody end with Shirakawa would be a better ending than living without him. It’s the first real touch of Satô’s mastery in the already strong film, and the first real indicator of where he’d take his narratives in Muscle and Hunters’ Sense of Touch.

Bondage Ecstasy requires such a literal rundown in the context of Satô’s other gay films because they lack such easy narrative readings, instead using the basic ideas laid out in Bondage Ecstasy to create bizarre, nightmarish tales of loss and obsession. In both Muscle and Hunters’ Sense of Touch, the stories also focus on men searching for their lost loves through a web of rough sex, but their portraits of obsession and attempts at capturing their leads’ fantasies are nowhere near as simple as Bondage Ecstasy.

In Muscle, the protagonist Ryuzaki is a photographer for the bodybuilding magazine ‘Muscle’ who enters a brutal S&M relationship with one of his sculpted subjects, Kitami. After a particularly bloody night of being on the receiving end of Kitami’s knifeplay, Ryuzaki finds himself overcome by the obsession to control and worship Kitami’s body, and with a single stroke of a sword, severs his beloved’s arm. Then, after a long stay in prison, he’s let out with only one goal in mind - to track down and rekindle his relationship with the only man he could ever love. Meanwhile, in Hunters’ Sense of Touch, the openly gay private eye Yamada is called on to investigate a series of killings where men are tied into strict shibari, murdered, and then castrated. The prime suspect? His ex from ten years ago, Ishikawa, the man he still fantasizes about every time he picks up one of his many casual partners.

In Muscle and Hunters’ Sense of Touch, the protagonist’s quests are driven less from ‘love’ and more from fetishization, chasing the high of their ex-partner’s touch, the thrills of their sex, the way they could hurt the protagonists’ bodies in the best ways. In Muscle, the longing is literalized by Kitami’s severed arm, perfectly preserved on his nightstand as Ryuzaki’s masturbation aid, a (literal) fetish kept to spark fantasies of his old lover brutalizing him in a blue-tinted dreamworld.

Ryuzaki’s fantasies are violent, but unlike Bondage Ecstasy, reality isn’t much better. Ryuzaki wanders the city in a haze, working at a dilapidated movie theater by day and hunting the shady backstreets for a one-armed man at night. His investigation only takes him to darker and darker places, and a chance encounter with a mysterious hustler ends with a brutal murder. Instead of the obvious narrative divisions between fantasy and reality in most of Bondage Ecstasy, Muscle only signifies its departures during sex scenes, which intercut between Ryuzaki’s passionless, mechanical ‘reality’, composed of some of the least genuinely erotic ostensibly ‘homoerotic’ imagery imaginable and the aforementioned blue-tinted fantasies of his imagined rekindling with Kitami.

For the most part, Muscle is content to let the leaps between the mundane and the surreal in its narrative all blend into one heightened state, leaving and returning to reality at will. At one moment, it’s capturing the (relative) mundanity of Ryuzaki’s searches and sex, and at the next, it’s become a full-blown ero-guro nightmare, with brutal mutilations filling in as romantic gestures. It’s a disjointed narrative filled with dead-ends and non-sequiturs, but if one thing is clear from Muscle it’s that it’s not the narrative that matters, but rather the oppressive mood it conjures up, and how that reflects on Ryuzaki’s mental state.

Hunters’ Sense of Touch, on the other hand, isn’t all that worried about capturing any sense of subjective reality. Sure, it pulls the Muscle trick of intercutting Yamada’s sexual encounters with blue-tinted flashes of his fantasies with Ishikawa, but even when the plot gets outlandish (psychics are involved), it never attempts to capture the dreamlike atmosphere of Bondage Ecstasy’s ending or Muscle’s entirety. Instead, it depicts Yamada’s obsession through the more straightforward elements of procedure, all but explicitly raising the question if Yamada wants to find his old flame to stop the murders, or if he just wants another shot at their relationship. The deeper Yamada gets, eventually taking on parts of Ishikawa’s life (in one memorable aside, he fantasies about being whipped by Ishikawa while Ishikawa’s wife begs Yamada to whip her in the real world), the more obvious his intentions become.

While most Satô films can only be compared to other Satô films, it feels hard not to see Hunters’ Sense of Touch as the flipside to Friedkin’s masterful American giallo Cruising, another movie about a detective investigating S&M murders. Yet while both the sex and the violence in Cruising is mostly used to shock the (presumably straight) audience, Hunters’ Sense of Touch goes as far to the opposite as you can get, playing both the sex and the violence for erotic appeal. We see Ishikawa’s - and later Yamada’s - obsession with mutilating their submissives shot through the same grammar we see the sex scenes, all tight closeups of necks straining against squeezing rope and switchblades tenderly caressing bulging briefs. Sure, filming murders like love scenes is as old as Hitchcock, if not older, but the way in which Satô attempts to visualize the compulsion of his villain, and later villain protagonist, has to be among the most brilliantly transgressive takes on the idea I’ve ever seen.

While both Muscle and Hunters’ Sense of Touch have heavy diversions from each other in terms of pace and content, they become a strange echo of each other when it’s time for the protagonists to confront the mysterious subjects of their desires. Unlike Bondage Ecstasy, these final meetings are the first time the films fully show the elusive figures outside of flashbacks, and in Hunters’ Sense of Touch, the reveal of Ishikawa is one of relief. He looks exactly like he did ten years ago, and is filled with remorse and self-loathing over his crimes. He’s a stereotype of a ‘good man’ turned killer, just a misunderstood innocent whose hurt and confusion drove him to eviscerate others, and whose soul can be redeemed by the love of the caring Yamada.

They embrace. They have sex. Yamada ties him up. And then he grabs Ishikawa’s switchblade. Through his journey, Yamada has discovered that his love for Ishikawa wasn’t necessarily for him as a person, but more for what he represented, the power he had over Yamada administered by rope and belt. He’s realized he prefers being it to craving it. Just like Steve Burns, Cruising’s undercover cop turned serial killer, he embraces the impulse, finally fully becoming Ishikawa by choking him to death and making him the first victim of the brand-new copycat killer.

While Ishikawa’s state in Hunters’ Sense of Touch is just as Yamada imagined, in Muscle, Kitami is completely different. He looks nothing like how he did in the flashbacks and fantasies (which also feature him with both arms), considerably more haggard and run-down. His sadism too has shifted from kink to full-blown cruelty in every walk of life, and upon seeing Ryuzaki in a bizarre, nightmarish stage performance, orders him to be tortured to death.

Ryuzaki’s confrontation with Kitami is defined by Ryuzaki having to finally face his actions, with the surviving cast of the film harassing him from the stage while Kitami interrogates him. “What do you even know about me?” Kitami roars, and it dawns on both the viewer and Ryuzaki that we don’t - the film gives us nothing to him until the finale except a muscular body and a good lay. Ryuzaki may love the idea of who Kitami was now, but he didn’t before. The question hangs.

“Your body,” Ryuzaki replies.

Bio:

Perry Ruhland is a queer independent filmmaker and critic with a passion for boundary-pushing cinema in fringe genres and movements. When he's not filming or screenwriting, he gushes about his favorite movies as a freelance film writer. Ask him about how good The Wild Bunch is.