Playing the Whore

Lake (Pier-Gabriel Lajoie) and his older lover Melvyn (Walter Borden) in Bruce LaBruce’s Gerontophilia (2013).

Playing the Whore: The Cinema of Bruce LaBruce

by Kyle Turner

Playing the Whore, which takes its name from Melissa Gira Grant's book on sex work and policy Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work, is a new column examining and surveying queer sex work in film, from Bruce LaBruce to Chantal Akerman. Playing the Whore seeks to interrogate ideas of power, eroticism, desire, capital, artifice, performance, pornography, politics, and film.

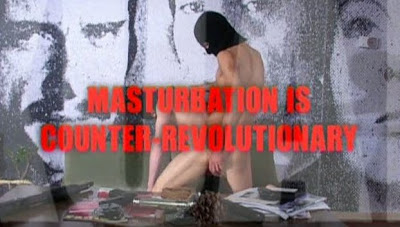

LaBruce’s The Raspberry Reich (2004).

In the world of Bruce LaBruce, there is no sexual revolution without homosexual revolution. An enfant terrible straight from Ontario whose ‘80s queercore and homopunk origins have defined his cinema, the raucous work of LaBruce posits that all of his characters, even when they’re not explicitly sex workers, are sex workers and laborers and, most important, revolutionaries.

Or we can think of these characters, and perhaps all good homos in (and out of) LaBruce’s cinema as, to use Gundrun Ensslin’s (Susanne Sachße) words, “terrorists”. In his book of criticism, Charlie Fox writes of John Waters’ films, “All [his] films provide explosive lessons about how queerness can be at once carnival romp and terrorist activity, rebelling against straight world notions of what’s normal with depraved glee.” The same can be said of LaBruce’s work, and it is Waters to whom he is in debt. Where they differ, and where LaBruce and certain filmmakers that burst onto the scene during the New Queer Cinema wave in the early 1990s, is the line they draw to connect aesthetic (dis)taste and a broader political critique. In films like No Skin Off My Ass, The Raspberry Reich, Hustler White, Gerontophilia, and The Misandrists, pornography is inextricable from propaganda. Sex and desire are tools for political thought, ideology, and critique of such. And everything is work, or work to dismantle institutions of oppression.

Though one might be disinclined to categorize any other filmmaker’s work as that of a “cinema of sex work”, except perhaps the directors for whom sex work is explicitly a recurring topic, I am drawn to describing LaBruce’s filmography this way because sex and work are intrinsic within the landscape of his films: not just the explicit nature of The Raspberry Reich and Otto!: Up with Dead People, but the way that sex and, shall we say, faggotry are constantly in dialogue with one another as political tools and paradigms. While non-explicit films like The Favourite or Klute can articulate the notion that no sex is apolitical with clarity and certainty, LaBruce’s sex as work, sex work, and sexual imagery is a means for him to weave in political thought and rhetoric. A scene in The Raspberry Reich between the kidnapped son of a banker and Gundrun’s boyfriend (whom she intends on queering!) is playfully, and aggressively, anarchic: Gundrun suggests the two fuck, and when they do, before an audience, the frame flashes with political slogans, superimposed onto the scene. “JOIN THE HOMOSEXUAL INTIFADA”. In No Skin Off My Ass, a scene between a hairdresser and the skinhead he loves in a bathtub contains voiceover from LaBruce about the nature of subcultures and their tendency to replicate social and structural inequality within their groups, in addition to manifesting their challenge to institutions, and perhaps failure to dismantle them, in aesthetics. And the pornographic film that is to be made by the Female Liberation Army (commandeered by Sachße’s Big Mother) in The Misandrists is itself a womanifesto, a training film, a call to action.

The women of The Misandrists (2017).

It is partially because of the films of Bruce LaBruce, as well as other works, that I became interested in trying to examine the landscape of films about queer sex work. That LaBruce’s films can meld the relationship between art film and pornography is a crucial starting point in terms of how he conceptualizes ideas of what sex, film, and labor are: even in a film like Hustler White, co-directed with photographer Rick Castro, he outlines these relationships in satirical tone and rough and tumble detail. Loosely based on Sunset Boulevard, Hustler White is the film that is most straightforwardly and explicitly about sex work as profession, following two gay hustlers in Santa Monica and the various clients they work with. LaBruce, who also stars in the film as a European writer named Jürgen Anger doing research for a book on pornography and prostitution (perhaps the name is a nod to Hollywood Babylon scribe Kenneth Anger?), swings ironically between the tedium of finding johns with Monti (Tony Ward) and a bizarre, heightened, even noir-ish sense of scenario. The line between Anger’s, whose unreliable narration guides the film, fantasy, and reality, what he imagines of sex work and the actual day to day job, is heavily blurred, shaped, undoubtedly, by the films he’s seen.

Tony Ward as Montgomery “Monty” Ward in Bruce LaBruce & Rick Castro’s Hustler White (1996).

Well known for its controversial scene involving an amputee client, however transgressive LaBruce is inclined to be, there is, nonetheless, a striking understanding of the intimacy that is curated and fostered, if need be, between sex worker and client. Crucial to this, LaBruce’s filmography, and this essay series more broadly, is what role difference plays: so much of queer identity, or even casual flirtations with queerness (say, gay4pay), create an aspect of identity and experience that exists in opposition to normative narratives of sex, work, and, in the context of this series, even cinematic techniques. So, certainly, at first glance, the sex scene with the amputee is unusual, something rarely afforded screentime, and differently abled bodies are barely given agency, never mind sexuality, but the scene is surprisingly tender. Beneath lime green light, the amputee says, “I’ve been looking for someone like you.”

Curious, within the presentation of sex work in film, is the language of it; not just the terminology, but the nonverbal communication, particularly the looking. What does looking say about our difference? How frequently are stories about sex work interweaved with stories of longing? This queer gaze applicable to LaBruce’s oeuvre oscillates between earnest and ironic at a whip-snap’s moment, such as in The Raspberry Reich, where the dynamic between two lams on the run post-kidnapping (the rich banker’s son adopting the name Clyde Barrow, a clever subversion of Warren Beatty’s originally written as impotent character in Arthur Penn’s 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde) is genuine, authentic love, and Gundrun’s monogamous and child raising relationship wickedly satirical, given that such a familial structure is antithetical to her professed belief system (she’s just as bourgeois as the people she claims she wants to destroy). A joke comedian George Civeris tells is this: “Hypocrisy is a big part of gay culture, so if you call me out on that, that’s hate speech.” Bracingly, LaBruce is compelled to unearth the complicated and contradictory nature of queerness and queer culutre, its various intracasies not unlike a landscape in itself.

With landscape in mind, it should be of note that Hustler White is about topography, about the landscape of hustlers and of Santa Monica Boulevard itself, sweltering in the heat. One wonders if it’s the hustlers burning up or if they’ve set the place on fire. Collectively, LaBruce’s films provide a road map to understand these various intersections and topographies: desire, eroticism, capital, fantasy, gender, work, artifice, authenticity, camp, intimacy, queerness, radical politic, genre, and cinema itself. This series of essays will attempt to explore the ways in which film can unpack and interrogate these intersections, contradictions, and complexities, about sex and work and film. Though Bruce LaBruce’s films span from the early 1990s to the 2018, crucial to this survey will be how the politic of queer sex work in film has changed or not changed, how our understandings of power and identity shift over time. And while heterosexual prostitution and sex work is a subject that is frequently the subject of film and film writing, there seems to be an absence of work examining LGBTQ sex work specifically. What of the temporal looseness of Funeral Parade of Roses, the narcoleptic fever dreams of My Own Private Idaho, the treatise of self and mobility in Tangerine, the patience of Je Tu Il Elle, the period lusciousness of Knife + Heart, or the emotional masochism of Fox and His Friends? In the cinema of queer sex work, business and pleasure aren’t so simple. In a post-FOSTA-SESTA landscape, where sex workers are even more vulnerable, there’s a world of difference and defiance when playing the whore.

Toshio Matsumoto’s Funeral Parade of Roses (1969).

Bio:

Kyle Turner is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn, NY. He is a contributor to Paste Magazine, and his work has been featured in The New York Times, The Village Voice, Playboy, Brooklyn Magazine, Slate, and Esquire. His work focuses on identity and issues of queerness and race. He is relieved to know that he is not a golem.

Twitter: @TyleKurner