You won't escape from your unconscious

Desire, drugs, violence, fear and obsession in Gaspar Noé's ENTER THE VOID, LOVE, & CLIMAX

Sex is where the unconscious is. In sex we may escape from reality, but not from ourselves. Everything that we are in public, we are as well in bed. Our lacks, our traumas, our desires – from the purest to the sickest – we find them all there, setting fire to our body. The only way to really escape them is to turn off the body, and turn to stone. The only way not to feel sad is to not feel. But Gaspar Noé's characters cannot help but live fully and risk everything, they're vital even in their nihilism.

Argentinian-born French filmmaker Gaspar Noé is one of the most controversial, desecrative and narcissistically provocative artists of the image of our century. You love him while you hate him, and this is exactly what he wants. His movies are always crossed by a path of despair and distress, but his characters are always moved by the strongest need for life. They go deep into their feelings and physical sensations, being unconsciously brave. “There is an energy of life or course that fights for the survival of the species, so whatever keeps you alive is good for the survival of the species. There is a meaningful energy which is the sexual energy,” he said in an interview in The Huffington Post in 2017. Most of the time, sex in Noé's films is not treated as mutually intimate or tender, but as an obsessive act, a laceration, an heartbreaking event in which two or more bodies pour out everything they feel with their residual energy, doing it violently (Irréversible, 2002) or in a moment of shared loneliness (Enter the Void, 2009), or in a fit of passion—spitting out their feelings and hitting each other with their love (Love, 2015), or losing themselves in a whirlwind of drugs and hallucinations (Climax, 2018), always exposing their Oedipal and most instinctive and delusional feelings (Seul contre tous, 1998). Noé's style turned into a brand, focused on his audiovisual virtuosity, with turbulent camera movements and detailed and disturbing sex scenes.

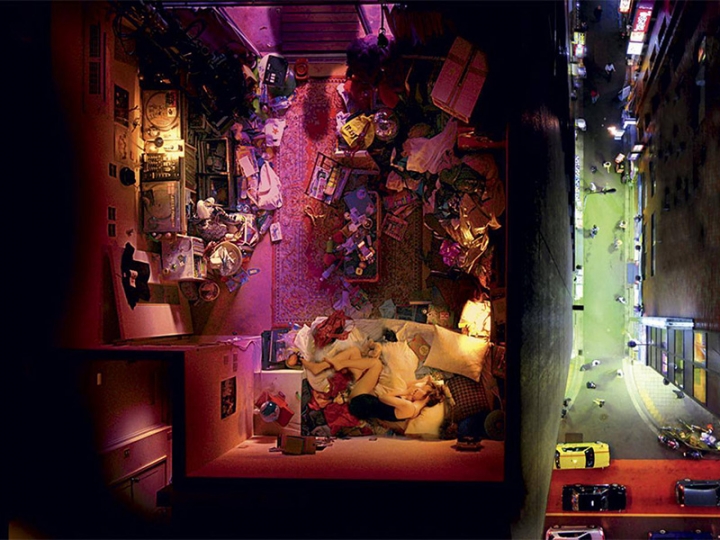

I would like to focus on the most recent three of these movies, as I like to give most of my attention to our cultural responsibility in a present that I feel so urgent. Enter the Void is an absolute mad psychedelic trip into the last days of life of a twenty-year old boy, Oscar (Nathaniel Brown), who lives in a very small apartment in Tokyo with his sister Linda (Paz de la Huerta). He deals drugs for money to survive, she works in a strip-club and is in an unhealthy relationship with her pimp. Enter the Void is an exhibition of the vacuity of human existance in neon lights. Sex is a dirty catharsis, a dense bath of deranged brilliance, an outlet of uncomfortable feelings; the place of memory, where acid is thrown on the wounds while the wounds hope to be healed somehow.

You watch this movie like you're living a physical risky experience, finding yourself in a vortex of frustration, obsession and death, looking through Oscar's eyes and his lucid unconsciousness. Enter the Void, as almost all of Noé's films, doesn't have an end, a real goal: we just don't understand where are we going and why, but what makes us keep staying there in front of the screen is the carnal, sexual consistence of the whole narration. Sex and neglect are the two sides of the same coin.

Sex is where every character fills in their blanks, runs desperately out from the silence, becoming addicted to it. Oscar and Linda are connected by a heartbreaking love; apart from that, there's no real love in any of these relationships. Linda, Oscar, Alex, Victor, Mario and the others they are all fighting for their survival. Everybody is vicious, ferocious in their way. Enter the Void is an immersive, audiovisual experience, down to the depths of human flesh. The conception of Linda and Alex's son merges with Oscar's birth, confirming the blood connection that binds him to his sister, that weird and forbidden—yet completely natural—desire he feels for the women of his family. The beauty of Linda's character, in particular, lies in her spontaneous, sincere and open, childish sexuality, which makes her completely genuine but at the same time even more vulnerable. Recently arrived in Tokyo, drunk, she tries to kiss his brother Oscar on the lips, while he rejects her: “Why? I missed you. I just missed you so much.” “I feel so free... Promise me you'll never leave me,” she’d told him earlier. Oscar and Linda had already made a blood pact when they were children, after seeing their parents die brutally in front of them: they would never leave each other, death would never divide them.

A pact between a woman and a man is also central in Love. This time it’s not a blood pact, but a drug pact: “Keep it for... if something bad happens in your life and I'm not there. It will protect you,” says Electra (Aomi Muyock), while giving opium to her boyfriend Murphy (Karl Glusman). They promised to protect each other from everyone, and to never leave each other. Sex between two people who love each other is amazing, and is never too much. At some point in their relationship, drugs and other sexual partners start to weave into their love and sex, making them gradually move away from each other and from themselves. They become angrier, sadder and lose inspiration for making their art – she is a painter, he is a filmmaker. Electra and Murphy are two very passionate human beings – in other words, they are junkies. They both easily lose control of their own fragile desires which become real obsessions: everything they try and like, lonely or together, they want to try again, and again, getting intoxicated, until they make another deal, trying to promise each other they will act better and more reasonably from now on. But, actually, they both act like kids and do the same bullshit, in different ways, until things really get worse. Electra and Murphy are, in the end, both lost in space and time, and maybe that's why they love each other so much.

In Love, their story is told by the voice of Murphy's regret, through a long flashback: “I'm a loser...yeah, I'm just a dick. A dick has no brain. A dick has only one purpose: to fuck. And I fucked it all up.” The weakness of the flesh led to the reckless waste of such a great love, of such a wonderful interlocking of bodies – the right one.

What we have to highlight in Gaspar Noé's work is the focus on sexuality in a very original and personal way. He may be narcissistic, but he's never trivial, and he did something nobody ever did before: representing explicit, real sex with real feelings at the core of it – be they positive or negative, violent or sick, tender or perverse. Gaspar Noé talks about the human experience without judging it, without separating the good from evil. He's just free. He could actually be a valid alternative to mainstream pornography: even if the two have in common a strong male gaze, the second one is without content, without any valid feeling, and just inhuman and far from reality.

What Enter the Void and Love have in common, as we just said, is the overbearing male perspective and a resigned bottom in/submission of the female characters. Beautiful female bodies have a lot of space in Noé's movies (it's the case of Monica Bellucci in Irréversible, as well), but we never see a female orgasm, or a totally visible vagina without a penis near her: what matters is what the man does with that vagina, or how he ejaculates inside her. The main characters are men who cannot control their desire for women – they are their victims and executioners – along with women who like to fuck and are “sexually active” (as men like), but what these women really want and think is not that relevant in the plot. It seems like women bodies are absolutely showy, but essentially silent. So here is Noé's only limit: representing human relationships and sex only through his male gaze. If women, in his movies, were protagonists and not just perfect bodies that deal with pain and suffering by taking drugs; if they were not only men's vice and condemnation, but complete personalities with a rich inner voice, an infinite silent force and an extremely complex sexuality (as they are in reality), the films of Gaspar Noé would be absolute masterpieces.

So, let's go ahead. 2018 is the year of Noé's ultimate movie, Climax, which many critics have already considered a summary of his cinematic style. A group of charismatic dancers set up a party in a gym inside of a disused college. Here again, drugs are the origin of internal conflicts and between the characters: someone dissolved LSD in the sangria, and that's the beginning of a trip into a paralel world, where happiness and excitement turn gradually into sentimental and sexual frustration and violence. Sex finds in drugs’ effects its total expression, showing the demons we usually hide, while we lose control of our behaviour. Once again, Gaspar Noé gets us away from society, from the “politically correct”, to show us the monsters we animal-humans all have inside, externalizing them: our deepest and darkest passions, our addictions and dissatisfactions, our emptiness, the urgencies of the flesh – that's why they are so disturbing, like a punch to the gut. Brutality, hate, thirst of death, they explode all against all, through uncontrolled compulsions and excess, blood, fire, tears, ultraviolence, destruction with no limits.

Differently from the other two movies we analysed and the preponderant male gaze we mentioned, the lead character here is a woman, Selva (the absolutely extraordinary Sofia Boutella), a young choreographer, and both female and male sexuality and instincts explode with the same intensity. The outstanding and sensual coreographies make this movie hypnotic and orgasmic. The hungry camera chases the dancers, using the space skilfully, being obsessed by their sinuous and beautiful bodies that run wild, intertwine and lose themselves, to the rhythm of deafening, captivating music: an orgy of sounds and dances. It's one of the most intense movies of the year. Again, we're admiring an aesthetic experimentation without any pretension of telling a complete and linear story. We cannot expect positivity or some rational hidden message.

Gaspar Noé provokes our eyes and electrifies our veins by exposing our unmentionable fears and desires, our most disgusting and shameful needs, without wanting to teach us anything, offering us a unique audiovisual experience. There's always a forced and coercive direction in Gaspar Noé's drama. Life is contaminated and decomposes into delirium and death. If there's a lesson we can learn from his art, it’s that we cannot run away from ourselves and our unconscious. And sex is the (un)safe space where we can get to know everything our body hides to the outside.

Bio:

SARA MARRONE is a hybrid actress, performer, author, freelance theatre and cinema critic. She believes in the power of arts to communicate change and to empower people everyday. Since 2017, Sara is the art director of the multidisciplinary artistic platform PLEASUREisPOWER, boosting the talk about pleasure, desire, sexual identity, and gender. She also co-starred in the post-porn short movie "Un'ultima volta (The End)", directed by her girlfriend, Charlie Benedetti, and produced by Erika Lust.

Instagram: @sssarabrown

Twitter: @unaSaraMarrone

Facebook: PLEASUREisPOWER